Do users really follow the paths carefully mapped out by designers? And when reality goes beyond the scope of the design—which happens more often than we think—how can we know this other than through intuition and assumptions?

On a daily basis, business-oriented software supports very concrete activities: managing leave, processing absences, tracking careers, producing regulatory reports, etc. In terms of design, these activities are translated into well-defined paths, supported by workflows, management rules, and functional test specifications. In practice, it’s a different story: agents negotiate with emergencies, organizational constraints, local customs, and tips passed on between colleagues. Sometimes they follow the procedure to the letter, sometimes they don’t, but the work gets done anyway.

Between these two worlds—the ideal scenario and the reality of the work—lie gaps in usage that we often sense empirically (we know that things are not going exactly as planned) but rarely measure rigorously. The goal is not to blame users or to sanctify specifications, but to understand what these differences reveal about the quality of user journeys, the ergonomics of systems, and the evolution of business practices.

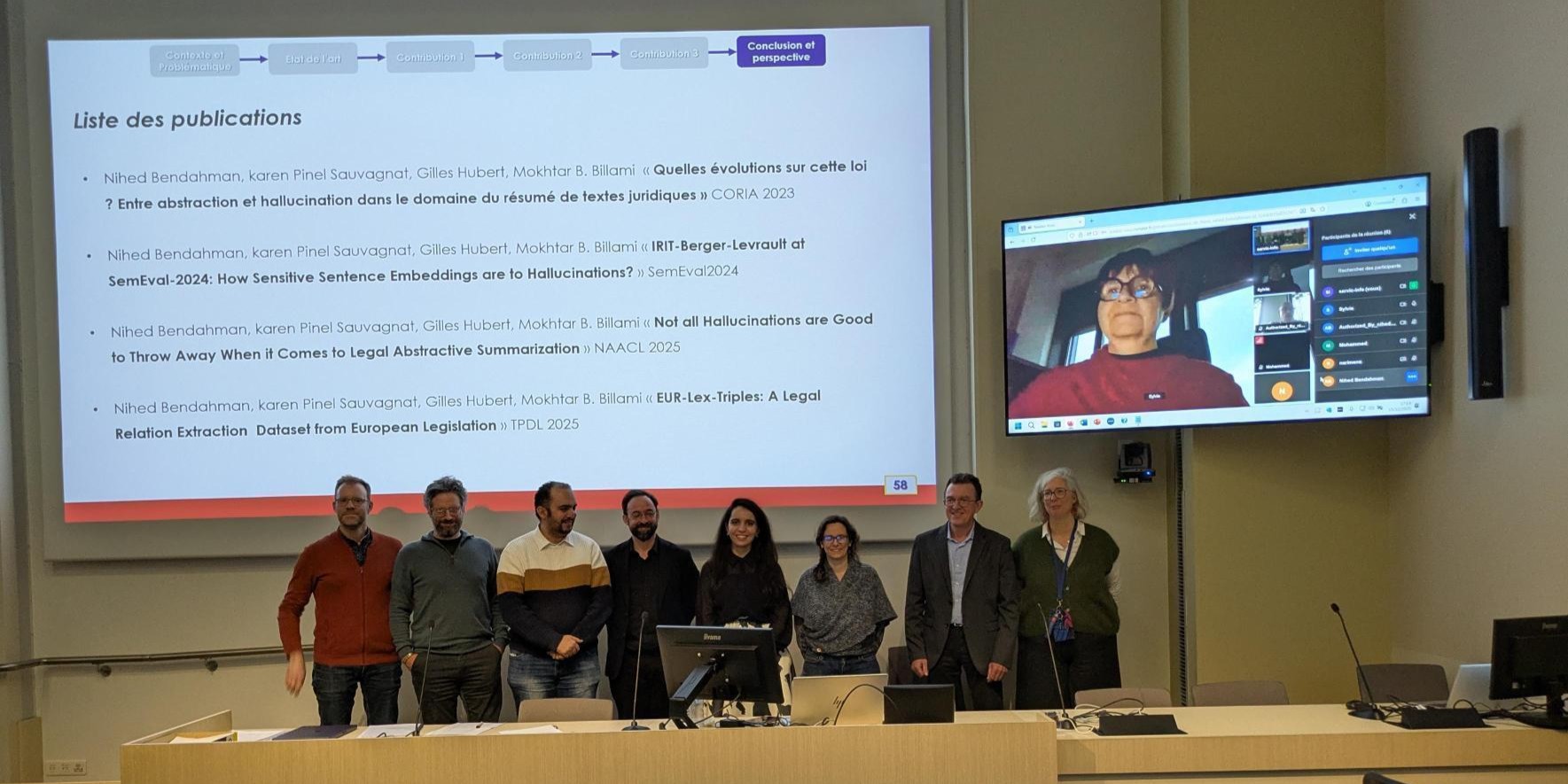

This article is the first in a two-part series. Here, we discuss these usage deviations in general terms: why they occur, how they affect design, and why they are valuable rather than annoying. In the second part, we will see how these ideas have been put into practice in a concrete case: SEDIT, an HRIS from Berger-Levrault, and how we measured these deviations based on actual usage traces.

1. The ideal user… does not exist

In functional specifications, everything is neat and tidy.

Business-oriented software is designed to follow well-defined paths: step 1, then step 2, then step 3. Everything is described in test specifications, validated, and traced. On paper, the user follows a smooth, almost academic scenario.

Reality rarely looks like that.

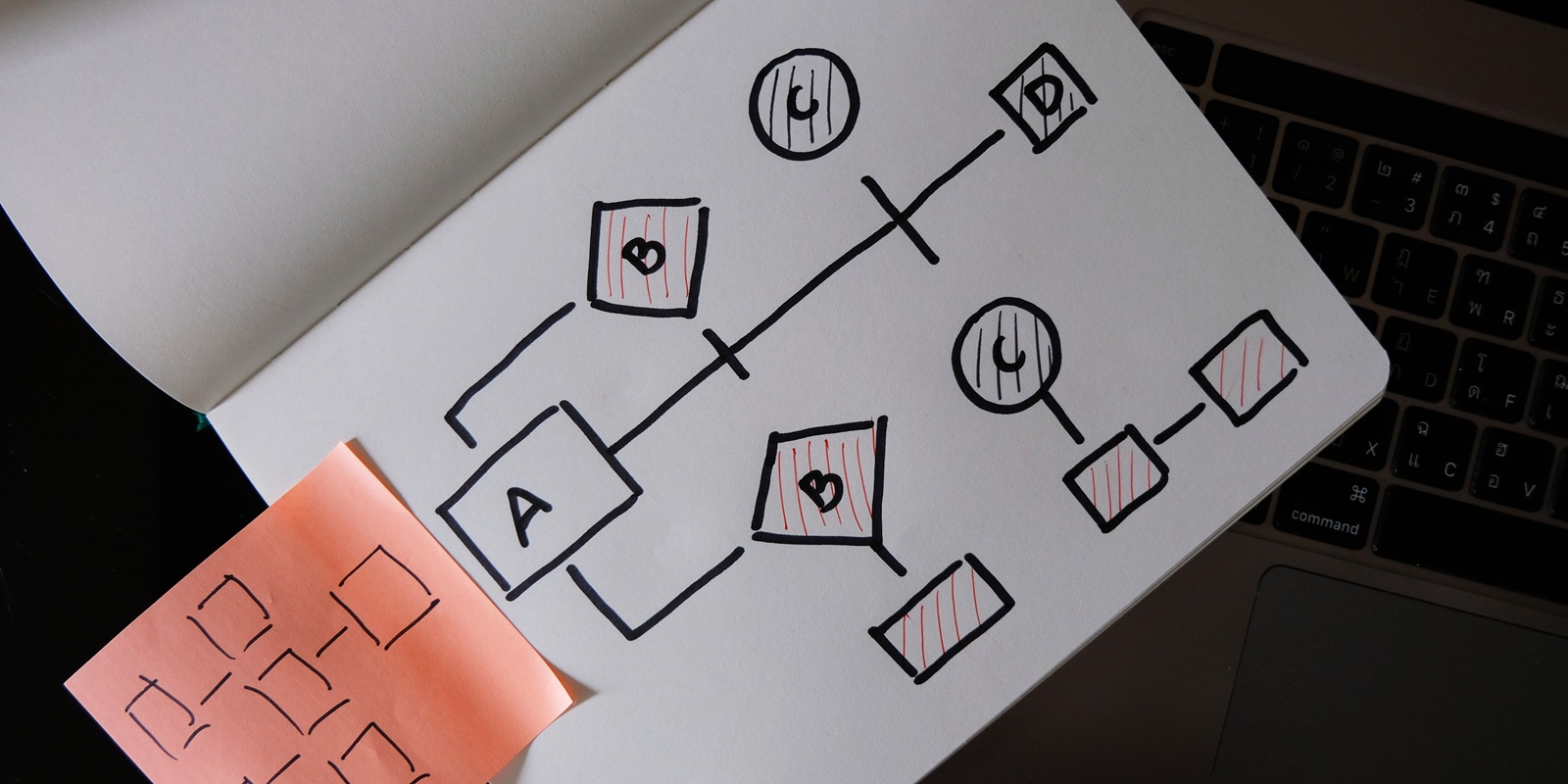

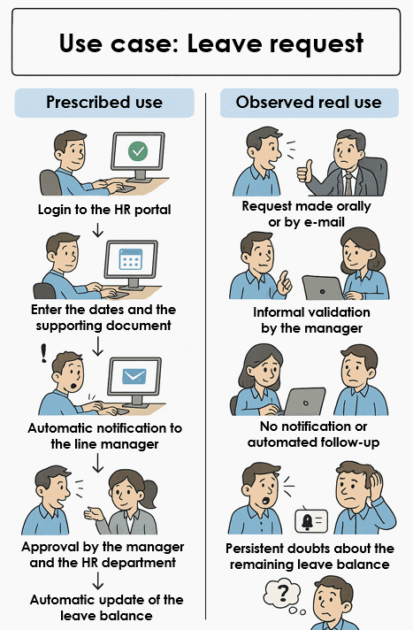

Let’s take a very simple general case (Figure 1): requesting time off. In the prescribed use version, the employee logs into the HR portal, enters their dates, adds supporting documentation, and submits the request. This is automatically notified to their manager, who approves it in the same tool. The time-off balance is updated, and that’s the end of the story.

In the actual use version, things happen differently: the employee first discusses it with their manager at the coffee machine or by email, approval is given verbally, and the request is entered into the software later… or not at all. The system then only sees a small part of the social context surrounding the leave request.

In ergonomics, there has long been talk of prescribed work (what we are asked to do) and actual work (what we really need to do to make it work). Applied to business software, this gives two sides of the same coin: on the one hand, the prescribed use, modeled in the design; on the other, the actual use, observable in practices and activity traces.

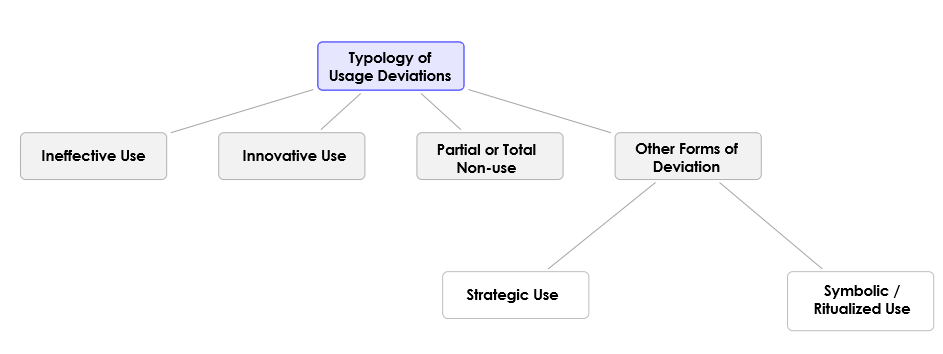

The literature distinguishes several ways of deviating from what is intended (Figure 2):

- Inefficient use: following the procedure, but incorrectly or in the wrong order, with re-entries, unnecessary detours, and extra clicks.

- Innovative use: repurposing the tool to work more efficiently, combining functions intended for other purposes, inventing local routines.

- Partial non-use: the system is circumvented, certain steps are replaced by emails, Excel files, informal conversations;

- Strategic or symbolic use: we do “just enough” to satisfy traceability requirements, while actually working elsewhere.

Our goal is not to label each behavior, but to start with a simple and very concrete question:

What do these deviations tell us about how software is really used, and how can we leverage this information to improve design?

2. Why these deviations are valuable for design

At first glance, a deviation between prescribed and actual use looks like a problem: the procedure is not being followed, the intended workflow is not being followed, the tool is not being used “properly.” However, when we look more closely, these discrepancies often tell a different story: that of users who “get the job done” in a constrained environment, with tools that are sometimes incomplete, sometimes too rigid.

The same discrepancy can mean several things:

- An ergonomic friction point: if everyone “forgets” a step, it may be because it is poorly placed, poorly understood, or perceived as unhelpful.

- An intelligent adaptation: a shortcut, a trick, or a recurring detour may reveal a more efficient way of sequencing tasks.

- Organizational dissonance: when software imposes a logic that no longer corresponds to the reality of the job or collective practices, users fill the gap as best they can.

Rather than considering these discrepancies as simple compliance issues, they can be treated as weak signals:

- Friction signals: where software slows down or complicates work.

- Signals of innovation in use: where users invent new sequences or uses that were not anticipated.

- Signals of business misalignment: where the rules coded into the system no longer reflect the reality on the ground.

For a designer, publisher, or product manager, these signals have several implications:

- Rethinking test scenarios: if test specifications only cover quasi-ideal paths, they validate compliance with the specification, but not relevance for dominant uses. Usage discrepancies invite us to enrich these scenarios with paths that have actually been observed.

- Adjust functional paths: frequent detours, recurring screen combinations, and systematically bypassed steps point to areas where navigation, function groupings, or sequences can be redesigned.

- Prioritize changes: when significant actual usage relies on workarounds (emails, exports, third-party tools), this indicates an unmet business need that may justify a priority product change.

- Improve the user experience: by integrating these actual uses into the design, we reduce everyday irritants, simplify flows, and make the system more aligned with the reality of the work.

Usage discrepancies will never completely disappear, nor is this desirable. They demonstrate the flexibility and resilience of organizations: when the system does not cover everything, the collective invents solutions. The challenge, from a design perspective, is therefore not to track down and eliminate all discrepancies, but to know how to “read” them: which ones reveal a flaw in the software? Which ones, on the contrary, reflect an interesting innovation? Which ones signal a gap between prescribed rules and business reality?

To answer these questions, it is no longer enough to observe with the naked eye. Today’s digital systems produce a significant amount of usage data (clickstreams, activity logs, navigation graphs) which, when properly analyzed, can be used to quantify these discrepancies and identify recurring behavioral patterns.

In the second episode, we will see how our approach was implemented in a concrete case: SEDIT, an HRIS from Berger-Levrault, used in public administrations. We will move from general principles to practice: how we reconstructed navigation paths from traces, how we projected them into a latent space, and how we quantitatively evaluated the place of prescribed scenarios among actual uses.