This article by Valérie follows on from a previous one describing the innovative Living Lab set up at Berger-Levrault. As a reminder, this innovative, user-centered approach aims to optimize the development of appropriate, useful solutions that respond directly to the real needs and challenges encountered in the field by customers and users of our software. Here are some concrete examples of how this approach has been put into practice:

- and the project to develop the Intelligent Assistant for the Legibase legal search engine, designed for local authorities.

- the project to design the MAPAF intermediation platform, dedicated to structures in the medico-social sector,

Living Lab Applications – A view of some Innovative projects

MAPAF – Intermediation Platform by a Medical-Social Structure

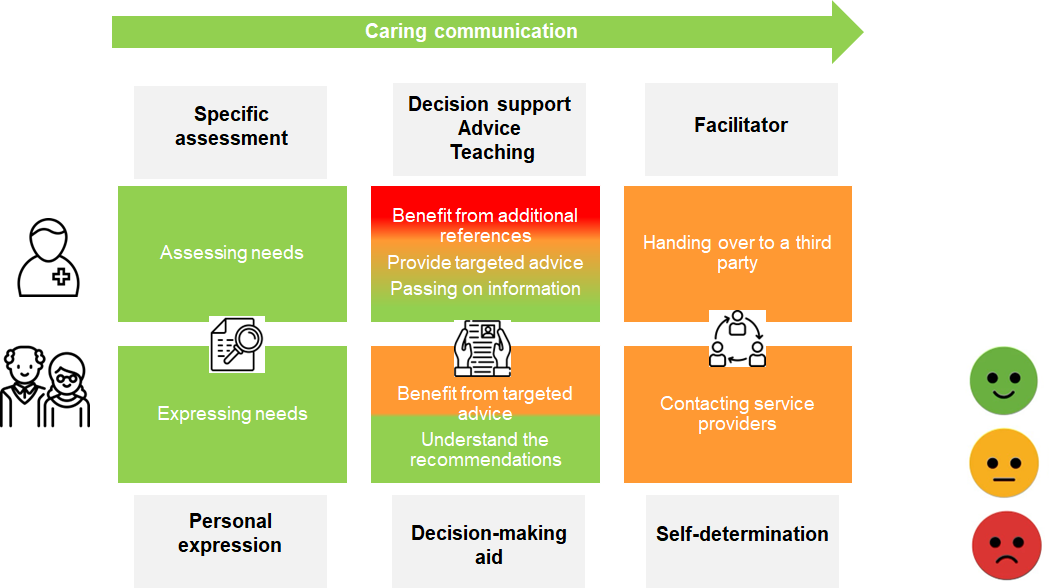

An in-depth evaluation of the MAPAF (Mission d’Accompagnement des Patients et Aidants Familiaux) platform was carried out. The latter combined a short-term analysis of the feasibility of its use by users with a long-term assessment of its transformational impact on professional practices and the structuring of the organization in charge of its deployment.

The MAPAF platform aims to identify the needs of patients we want to maintain at home. It aims to recommend personalized solutions to support them and their family carers, in order to avoid disruptions to their care. The evaluation was carried out over a two-year period, involving 60 patients and 5 healthcare professionals. It was based on a multidisciplinary approach involving ethical, technological, economic and organizational dimensions. It was therefore necessary to measure the feasibility of use, the added value and the impact of the platform on professional practices and on the organization of the deployment structure. After 5 months’ use of the platform, professionals were consulted by means of closed questionnaires, i.e. offering a set of predefined answers.

The results of the MAPAF platform evaluation provided tangible evidence of the feasibility of using the platform by medical-social professionals, while also highlighting several concrete benefits. In particular, the platform has enabled better detection of patients’ needs. However, the experiment revealed limited performance in relation to the needs of user professionals. This technical weakness hindered its full potential as a decision-making and self-determination tool.

The evaluation therefore provided key recommendations to decision-makers in terms of reorganizing business practices to facilitate the implementation and adoption of the platform within the healthcare structure. Among other things, we can mention the enrichment of the database entrusted to a dedicated professional, and the implementation of a specific organization to guarantee efficient and fluid management.

Intelligent Assistant by Légibase Collectivités Customers

An assessment that reveals the strengths and needs not addressed by innovation. It extracts key data to inform decision-making on the future of this innovation.

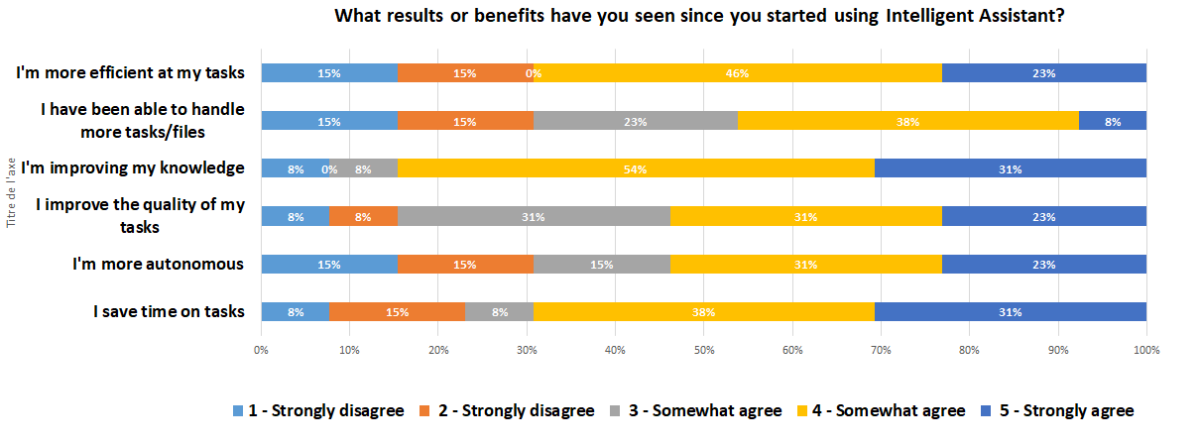

The objective was to test the integration of an Intelligent Assistant using Artificial Intelligence (AI) in beta version with Légibase Collectivités. We wanted to identify the brakes and motivators to the adoption of the AI, and analyze its impact on users. This study was based on a qualitative approach, including in-depth interviews with 15 customers using the AI.

The study showed that the AI saves a significant amount of time thanks to its responsiveness and the relevance of its answers. It optimizes the search for information by avoiding useless sources and efficiently directing users to appropriate references. The AI facilitates access to data by automating the identification and consultation of sources, while clearly structuring the results. A real decision-making aid, it provides fast, precise answers, making it easier to deal with complex legal issues, while empowering users, who no longer need to depend on intermediaries. It also promotes lifelong learning by providing additional resources and making complex concepts more accessible. Finally, it helps to dispel doubts by validating information and ensuring that legislative texts are up to date, thus reinforcing the reliability and legitimacy of the steps taken.

Limitations of the Method

Engaging users in Living Labs remains a Major Challenge

A study by Lievens et al., 2014 [Ref 3] conducted on several Living Lab environments highlights an often-obscured reality: while the ideal of close collaboration between designers and users is laudable, the reality of participation turns out to be far more mixed. From the outset, the figures are indisputable. On a panel of over 19,000 users involved in various innovation projects, only a tiny minority – barely 1.1% – actually invested in a process of repeated testing over a four-year period. Conversely, over three-quarters of participants contributed just once before disappearing from the process.

Structural Difficulty in Maintaining a Stable, Long-term Commitment Dynamic

Among the explanations put forward is the natural erosion of motivation. Only users driven by intrinsic motivations – the desire to learn, the pleasure of contributing to innovation, or the satisfaction of seeing their ideas taken into account – persist over time. But this connection cannot exist without a match between participants’ expectations and the projects themselves. Commitment is strengthened when experiments resonate with users’ interests. Otherwise, users perceive their participation as a constraint rather than an opportunity. This inadequacy is sometimes coupled with a feeling of frustration: when feedback from users is not taken into account without explanation in successive development cycles, disenchantment sets in. Lack of follow-up and transparent communication on project progress reinforce this mistrust, gradually transforming initial enthusiasm into disinterest. Another obstacle lies in the very nature of the user experience within Living Labs. Unlike certain forms of participatory innovation, which incorporate playful or interactive elements, many of the tests carried out in these Living Labs are perceived as boring or tedious.

A lack of clarity regarding expectations, overly vague instructions or a lack of feedback on experimentation results in user fatigue and a gradual disconnection from the innovation process. Effective communication and support for users appears to be a key lever. Involving participants requires a subtle balance between support and autonomy.

Involvement cannot therefore be limited to a purely functional evaluation process: it must also give rise to a certain degree of pleasure, cognitive satisfaction, and even a form of ownership of the project. When this dimension is lacking, participation is reduced to a one-off act, deprived of any anchoring dynamics. It is essential to gain a thorough understanding of the mechanisms of voluntary involvement in Living Lab research, and how to implement the levers that will reinforce their intrinsic motivations (such as contribution, curiosity, etc.).

Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences (SHS) : a Strategic Lever for Overcoming the Obstacles of the Living Lab Method

User Involvement is based on a Complex Dynamic

Many research questions remain largely unexplored in this field. The work of Lievens et al, 2014 [Ref 1] has highlighted the importance of diversifying motivational levers, relying on factors that are both multiple and intrinsic. Indeed, user engagement is based on a complex dynamic that requires the simultaneous activation of several motivational drivers such as a sense of belonging or social recognition, curiosity, discovering new things, learning something new, increasing one’s own reputation within a network. The exploration of motivations is therefore essential to the advancement of the engagement issue, but should be seen as a starting point for further research into the mechanisms that reinforce intrinsic motivations, and the development of a theoretical model to better understand voluntary engagement in Living Lab research.

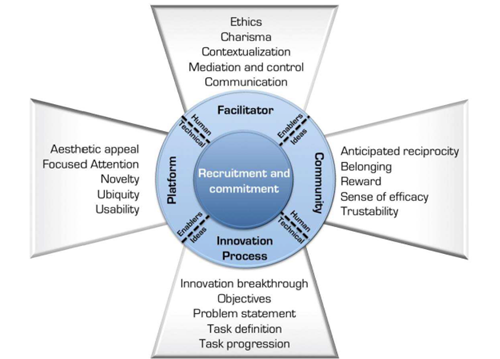

In this vein, the work of Bertoni et al, 2013 [Ref 2] has established a basic framework for recruiting and engaging users in innovation projects. This framework is structured around four key dimensions, providing a solid basis for developing a user involvement methodology (Figure 3):

- Innovation process : to encourage participation, it’s crucial to strike the right balance between the innovation’s level of maturity and user involvement. The activities proposed must be adapted in terms of duration, favoring short-term initiatives or breaking down tasks into micro-tasks, in order to maximize participants’ involvement.

- Platform : to encourage participation, the digital tool used to collect user feedback must combine security and attractiveness. It must be aesthetically appealing, while facilitating fluid, intuitive communication.

- Content : to engage users, it’s crucial to offer attractive, high-quality and timely content.

- Community : build a solid, engaged community by playing on four main factors:

- Create a community by innovation,

- Create small, well-defined communities that encourage interaction between members with similar interests,

- Provide regular, constructive feedback to users,

- Appoint a trusted facilitator to guide the community.

The work being done in SHS is both instructive and inspiring, and represents a real strategic lever for overcoming the obstacles of recruiting and engaging users, and it will be imperative to build on their advances to consolidate our Living Lab method.

Conclusion

Real-life experimentation with users is an essential step in the Living Lab approach. It is based on a multi-dimensional evaluation of the innovation, enabling us to analyze its adoption from different angles. By crossing these approaches, this analysis refines our understanding of the adoption process and offers a global vision of its potential, for both users and decision-makers.

The results obtained are invaluable resources for:

- optimizing the technical development of the innovation by integrating user feedback.

- guiding decision-makers’ strategies by facilitating scaling-up.

- detecting new directions or substantial improvements.

- securing its market launch by guaranteeing a better match with real needs and user expectations.

It’s important to remember that no innovation, however effective, can prosper if it comes up against cultural, ethical or practical resistance. By integrating the user into an active role, the Living Lab ensures smoother, more natural adoption of the technologies developed. This approach avoids the psychological or regulatory bottlenecks that frequently arise when deploying new solutions, and guarantees greater buy-in from the populations concerned. In this respect, the Living Lab plays an essential role in transforming uses and supporting change.

Lastly, commitment to a Living Lab cannot be decreed; it has to be built patiently, taking into account the psychological and social forces behind active participation. By cultivating a relationship of trust, valuing users’ input and offering them a stimulating and enriching experience, we can hope to transform a simple one-off collaboration into a truly immersive and lasting dynamic. In this respect, the contribution of research in the field of Human and Social Sciences is undeniable, and should be promoted in our internal practices.

References

[Ref 1] Drivers for end-users collaboration in participatory innovation. development and Living Lab Processes. Lievens, B., Baccarne, B., Veeckman, C., Logghe, S. & Schuurman, D. 2014., 17th ACM Conference on CSCW, workshop Designing with users for domestic environments,Baltimore.

[Ref 2] User recruitment and commitment in online living lab community. Bertoni, M. & Stahlbrost, A. 2013. SociaLL WP4 report, en ligne.